ADHD and digital accessibility with Sonia Prevost

When we talk about digital accessibility, neurodevelopmental conditions — such as autism, dys disorders, or attention-related conditions — are not usually the first thing people think of. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines were originally created to support blind users and later expanded to address other disabilities, including ADHD (Attention Disorder / Hyperactivity Disorder).

Worldwide, research suggests that around 2% to 5% of adults experience ADHD. ADHD is recognised as a disability in many countries when it significantly affects daily life. Yet we still often hear comments like: “Everyone’s a bit ADHD.” So what belongs to the disorder, and what is just part of everyday experience? That was one of the questions I asked Sonia Prévost.

I first discovered Sonia through her article One year of digital accessibility, where she talks about her career change from developer to accessibility consultant. As our conversations went on, I learned that she has ADHD. Her double perspective — as an accessibility expert and as someone with lived experience — made me want to share her story.

Listening to her, I quickly realised that ADHD is not simply about a lack of attention. It is a way of functioning that can shift between hyperfocus, impulsivity, coping strategies, and deep fatigue. For Sonia, it is also a strong source of creativity.

These variations in attention shape how she navigates interfaces. A carousel that spins endlessly. A form with no clear structure. A key action hidden in a personal account. Each of these elements can make her life easier… or much harder. My conversation with her is a reminder of how strongly design influences the attention and energy of the people who use our digital services.

Understanding ADHD

What is ADHD?

The formal definition is “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder”. Personally, I think hyperactivity is always there — even when you can’t see it in someone’s movements. Hyperactivity can also happen in the mind. I think the word “disorder” is actually well chosen, because it’s not just about being scattered all the time. It’s more that attention shifts depending on the situation. Sometimes you move into hyperfocus, with intense, almost total attention. And sometimes you feel completely scattered, jumping from one topic to another, from one distraction to the next, without being able to stop.

Having ADHD also means constantly seeking new things. There is impulsivity, more complex emotional regulation, and mental rumination. When your thoughts loop endlessly, it’s not that easy to switch them off.

And it comes with a lot of fatigue. Constantly managing attention, forgetfulness, emotional roller coasters, obsessions — it’s exhausting over time.

I also think it’s something very creative. For example, you never stop at one solution. When you face a problem, you look for ten different ways to get around it. So it’s not all negative, but it is something quite intense to handle.

If you could take a magic pill to make your ADHD disappear, would you do it?

Definitely not — I think I’d be too bored. Maybe at one time, before being diagnosed, I might have been tempted. Especially when I was struggling at work, socially, or as a parent. I probably would have welcomed a miracle solution back then, because when you don’t know why you react the way you do, it’s really hard to cope.

Once I started exploring ADHD as a possible explanation, it shed light on my whole life. It helped me understand all the times when I reacted intensely, or why I burned out so often.

Sometimes I wonder if I’ll ever find balance between my hyperactive phases — when I say yes to everything without thinking — and the moments of crushing fatigue, when I have to deal with all those “yeses”.

My therapist helped me see things differently: balance is never static. She described it as a plank resting on a wheel. To stay somewhat stable, you constantly shift your weight, leaning sometimes to the right, sometimes to the left, without ever stopping. That image really calmed me. It helped me accept that I don’t handle demands in a linear way, and to embrace my own rhythm: periods where I welcome everything with open arms, followed by moments where I refocus and say no so I can breathe again.

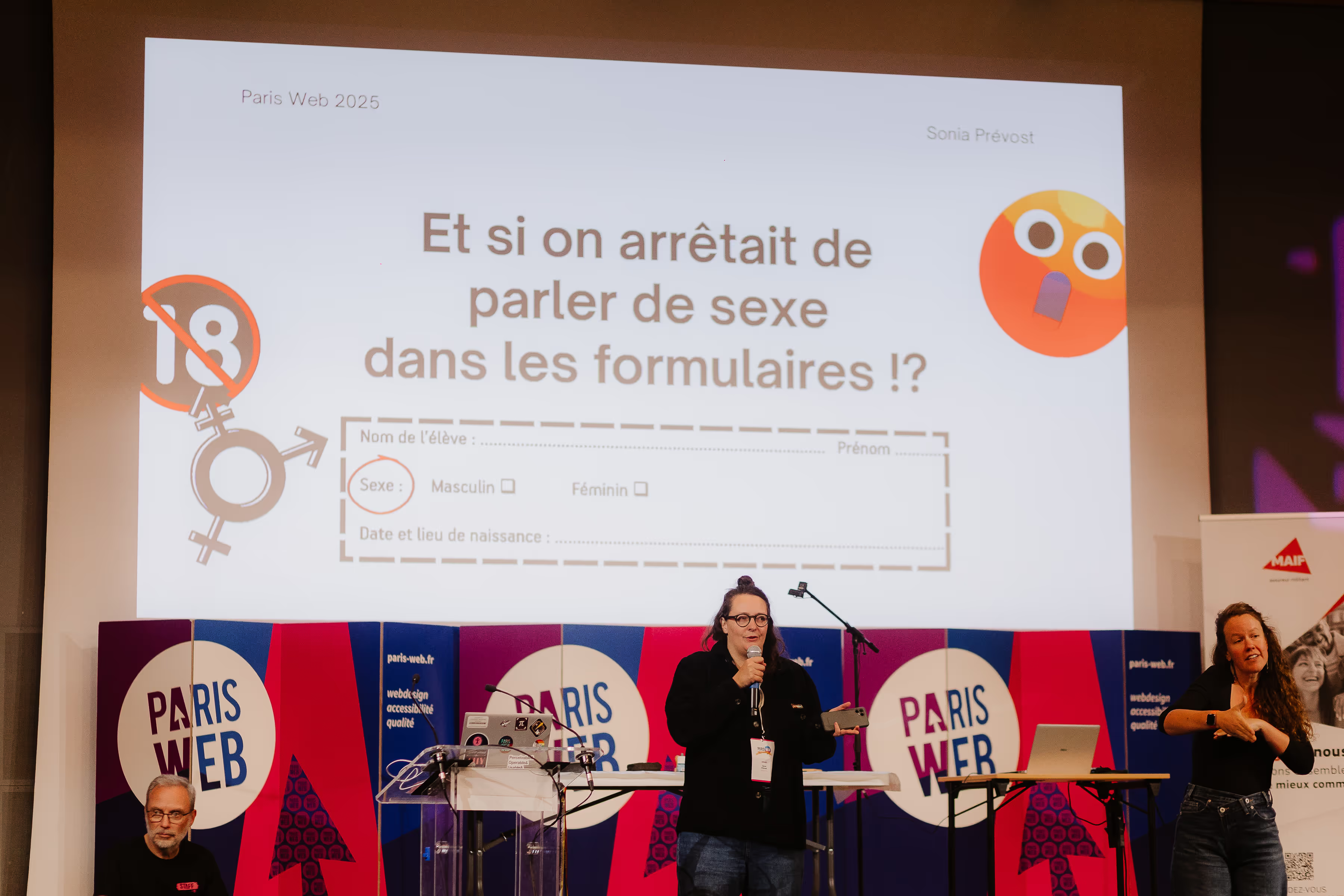

And honestly, the impulsivity that comes with ADHD lets me do some pretty wild things! Recently, for example, I decided in three seconds to apply for the Lightning Talks at Paris Web to show how absurd it is to ask about sex in forms. Of course I regretted it when it came time to prepare. But it was such an important message to get across that it was worth a weekend of stress and anxiety. And I really went all the way. I learnt my speech by heart, something I hadn’t done since primary school. I got on stage, it felt like doing stand-up, it was brilliant!

I’m not trying to be a superhero, but if I took a magic pill to remove my ADHD, it would feel like losing something that’s part of me. I’d feel genuinely orphaned.

How do you respond to people who downplay ADHD by saying things like “everyone forgets their keys”?

This is something I used to wonder myself when I first started looking into my own ADHD. I kept thinking that everyone forgets their keys. But now I can really tell the difference between forgetting your keys once because you’re tired, and leaving a pot of rice to burn until the fire brigade shows up because you went off to do something else in the meantime.

What really separates ADHD from occasional forgetfulness is the combination of factors: the attention issues, of course, but also the fatigue, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, obsessions, the constant search for new activities, and people-pleasing — saying yes to everything, all the time.

Some people might experience one or two of these symptoms. That’s why self-diagnosis isn’t enough, and why getting an official diagnosis matters.

A major part of the diagnostic process is what’s called differential diagnosis: understanding whether the symptoms come from ADHD or from another condition that looks similar.

Another important part is looking into your personal history: how you functioned as a child, whether similar traits appear in your parents or your children. In my case, people used to say I was a tired, strange child who was always daydreaming. And I can clearly see these traits in my father and my son too.

The tricky thing is that I can function almost normally when I’m not tired and everything in my life is going well. For me, the moment I started to seriously question things was when my twins turned five. I hit a period of extreme fatigue, and I couldn’t keep up all the coping mechanisms I had been using to keep the disorder at a distance.

It got to the point where I was forgetting my keys constantly, not just from time to time. I couldn’t manage my emotions anymore. And yes, anyone can feel like that when they’re exhausted — but with ADHD, it’s amplified a thousand times, with consequences that can be much more serious.

Identity and disability

Do you consider yourself disabled?

I still struggle to say that I’m disabled. I always feel like what I experience is nothing compared with other disabilities. But right now, I can see all the effort I’ve put in over the past year and a half slipping away — all the strategies I built to support my attention and manage the difficulties that come with ADHD. So yes, it is a disability. It affects both my professional life and my personal life.

To give a concrete example: I wear glasses, and without them I would be completely disabled. My glasses compensate for my short-sightedness. And it’s the same for ADHD. When I’m tired, I lose my “compensation glasses”, and that makes it very clear that this is a disability.

Do you use the words neurodivergent or atypical?

It’s complicated, because a lot of people around me use them, but I sit somewhere in the middle. I struggle with terms that immediately set you apart, or put you in a sort of “cool outsider” position — as if to say “I’m not like everyone else”. Some people talk about superpowers, but honestly, it’s not a superpower. It’s just a different way of functioning. And I feel like using those terms can make you sound like you’re trying to rise above the rest, and that doesn’t feel right to me.

At the same time, building a sense of community with people who function in similar ways is important. So having a shared term to describe this difference matters. If I compare it with Queer people, for example: their message isn’t “we’re better than everyone else”. It’s simply part of their identity.

ADHD is part of my identity, and it is nice to be part of a community. But we have to be careful not to fall into the trap of thinking we’re superior because we function differently — and that’s particularly difficult when the words themselves are “divergent” or “atypical”. As if on one side you have “normal people” and on the other, the “exceptional ones”.

Do you feel a difference in your relationships depending on whether the other person has ADHD or not?

It’s funny, because I’ve just said we shouldn’t draw lines between people… and yet I have to admit that conversations are often more fluid for me with people who have ADHD or who are neurodivergent.

To explain how it feels, I’m going to use an unexpected comparison: vinyl records.

When you listen to a record, the experience depends on the speed of the turntable. If it’s not set correctly, the music sounds too slow or too fast, and you lose the rhythm. With someone who has ADHD, it’s as if the turntable is set to the right speed. We’re on the same wavelength, and the conversation flows naturally.

With someone who doesn’t have ADHD, I sometimes feel like the speed is slightly off. It’s not about intelligence or value — it’s just the rhythm. The conversation feels slower, less spontaneous, as if we’re not quite listening to the same track. And I’m sure that from their side, I must seem unbearable: too fast, with sudden jumps and changes of pace.

There’s no “right” rhythm or “wrong” rhythm. It’s just that conversations are easier with people who share my tempo.

ADHD and working life

How does ADHD affect your work as an accessibility consultant?

I think we need to go back to the moment when I first realised that digital accessibility might be right for me. One of the questions I asked myself before switching careers was whether the job had enough variety or whether I would get bored.

Before that, I was a developer, and it no longer suited me. There were many reasons, and it wasn’t only about sexism in tech. My work as a developer felt very repetitive. You pick up a ticket, you build it, you run tests, you send it for review, and then the feature goes into production. I was full stack, so I saw lots of things, but the actions were always the same. I started to get bored. I needed more variety in my daily work.

When I discovered the role of consultant, I thought it was brilliant because I could do lots of different things: support teams, run training, carry out audits, and so on. Some parts are more routine, but two years in, I can say there’s enough challenge for me.

I was afraid I’d get bored during audits, but honestly, with developers’ creativity, I often find myself thinking, “Never disappointed, always surprised!” or “Oh, that’s a new one!”. I’m genuinely grateful for the creativity of developers because I never get bored.

My ADHD can still be a barrier because I can easily go off in all directions and struggle to prioritise. There is so much to do in digital accessibility, the topic is endless.

What remains difficult for you because of ADHD?

Prioritisation is extremely hard. I usually need someone’s help to stay focused. It’s not about checking my technical expertise. It’s about preventing me from dividing my attention across 130,000 tasks.

For me, everything feels urgent. Preparing an accessibility audit debrief feels just as important as running a design training session. I can’t tell which one should come first.

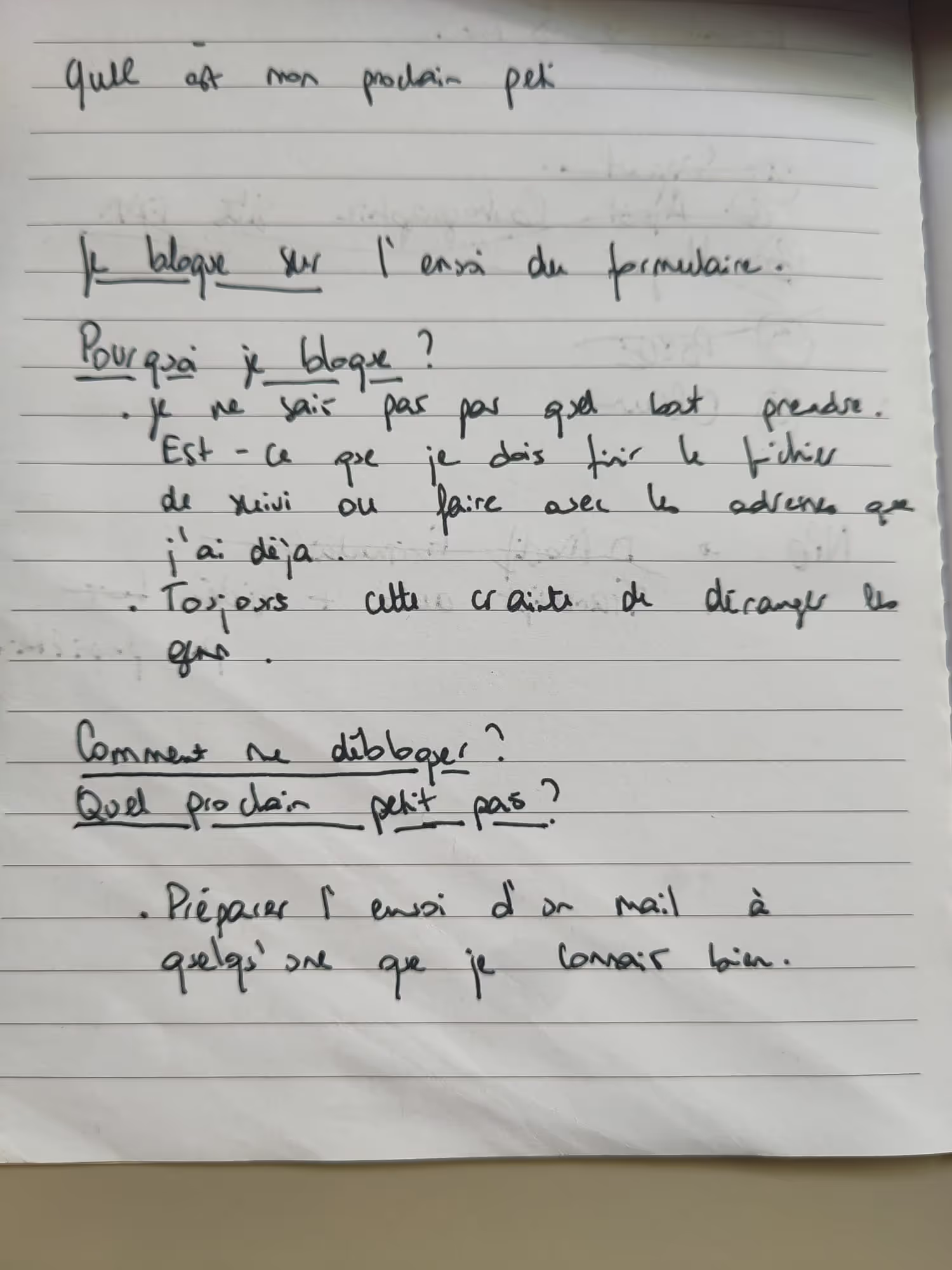

Another big challenge is task paralysis. One way of getting out of it is talking to someone to unblock myself. But that’s not always possible, so I try to reproduce that myself with a piece of paper. For example, I write: “I’m stuck on this task.” Why? “Because it leads to this.” Okay. “What’s the first tiny step I can take?” I retrace the mental steps on paper to unblock myself. I have a whole set of small processes like this to compensate for the effects of the disorder.

What’s funny is that I use the same approach with my children. When my son refuses to go to school, I don’t say, “You have to go, end of story.” I believe in step-by-step protocols. When a task feels impossible, you break it down into micro-actions. You start with getting out of bed, just that. Then a breathing exercise. Then putting on socks. Little by little, the movement starts, and the steps follow almost naturally until he finds himself ready, backpack on his shoulders, on his way to school.

UX design and ADHD

What makes using websites difficult for you as someone with ADHD?

There are a few things I explain during awareness sessions that are especially hard for me. For example, I remember having to show a carousel that moved automatically, and it was awful. I had to stay on that page to show something else, so I always tried to keep the carousel just out of view so it wouldn’t irritate me. Motion design or auto-advancing carousels aren’t a problem in themselves — but if you don’t provide a pause button to stop them, it drives me mad.

Long, multi-step forms are also very difficult for people with ADHD, who often have a weaker working memory and tend to forget what they entered between step 2 and the final validation. In my case, with forms like that, I spend my time going back and forth between steps to make sure I entered the right information.

What I really need is a progressive summary of what I’ve entered at the start of each step. That way, when I reach the end, I don’t have to rerun the whole process several times to check what I wrote.

And then there are forms that don’t tell me where I am on the journey. If you write “Step 2” without saying how many steps there are, it’s pointless. The cognitive load isn’t the same if there are three steps or six.

I also need to make the most of my concentration phases. A multi-step form can take all my energy. So sometimes I postpone tasks that I know will require too much focus or take too long.

Are there any RGAA criteria that directly or indirectly take ADHD into account?

For readers outside France: the RGAA is France’s official digital accessibility standard. It is based on WCAG, but the criteria are not identical — some rules differ.

There aren’t many RGAA criteria that mention ADHD directly. Most of them focus on other disabilities, especially visual, motor, and cognitive disabilities in a broader sense. But some criteria do help people with ADHD, even if they weren’t written with ADHD in mind.

For example, anything that reduces distraction is helpful. Criteria about controlling movement, limiting automatic animations, or providing a pause button make a real difference. If something moves on its own and I can’t stop it, it drains my attention straight away.

Structure also matters a lot. Criteria about clear headings, consistent navigation, and predictable layouts help me understand where I am and what I need to do. When the interface is unclear or keeps changing, I get lost and spend a lot of energy trying to find the right place.

And then there are criteria about forms: visible labels, clear error messages, and letting people review their information before submitting. All of these help reduce cognitive load, which is essential for people with ADHD.

So even though RGAA doesn’t explicitly talk about ADHD, many of its rules support attention, reduce overload, and make tasks easier to follow — and that helps me every day.

Further reading

- W3C – Cognitive Accessibility Resources (COGA): Guidance on reducing cognitive load, supporting attention, and designing predictable, low-stress interfaces.

- Making Content Usable for People with Cognitive and Learning Disabilities (W3C COGA Guidance): Practical advice on memory support, step-by-step tasks, clear structure and reducing distractions.

- Microsoft Inclusive Design Toolkit (PDF): Covers attention, executive functioning and cognitive effort through inclusive design principles.

- Neuroinclusive design for ADHD: A rebrand case study for an app supporting people with ADHD.

- The changing prevalence of ADHD? A systematic review: A comprehensive review of recent global research on ADHD prevalence. It shows that while demand for assessments has surged, the best-quality studies do not indicate a rise in ADHD prevalence since 2020.

- What the heck is ADHD?: Why scientists can’t seem to agree on one explanation by Anne-Laure Le Cunff.